I felt small standing amid the Roman ruins in Jerash.

I marvel at the building accomplishments of people who lived so long ago; they intended to make structures last. How many slaves gave their lives in constructing magnificence not even an earthquake could fully take away?

I think of how I’d stood in this exact place more than a decade ago, when war seemed imminent in Iraq and I was in Jordan, waiting for a visa to fly into Baghdad. Just as I was now.

Time seems fleeting – and not.

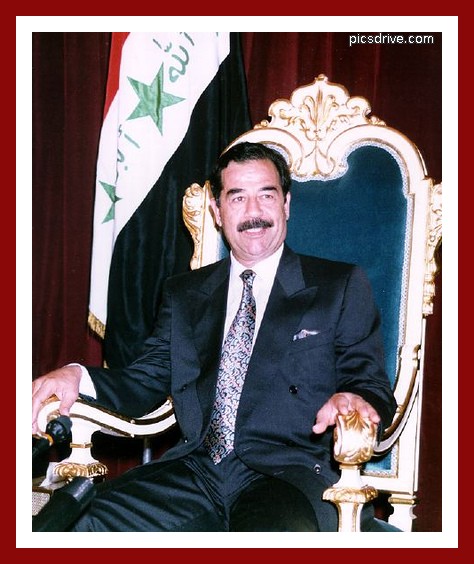

Back in December of 2002, no one knew for sure what would become of Iraq. How George Bush would invade, drop bombs, send the world’s most powerful military in to destroy Saddam Hussein.

No one knew what would come next – a de-Bathification program that purged Iraq institutions of knowledge and expertise and left an occupying U.S. force with the daunting task of running a nation.

No one knew how American soldiers and Iraqi civilians would fall. One after another. In roadside bombings, firefights and attacks from an enemy that was often unseen. Or how Iraq would fall into chaos; Sunni fighting Shiite to the point that everyone assumed the worst of a civil war.

I stand under a cloudless sky in Jerash. It is late February but the chill that is normal for this time of air is gone. It is warm. The sun, bright. Like in Baghdad.

I will be there soon, 10 long years after the first time I visited.

Saddam’s face was everywhere then, a constant reminder of the consequences of stepping outside the boundaries of subservient Iraqi life. I remember clearly when I walked down the jetway from the Royal Jordanian plane at Saddam International Airport. “Down With the USA!,” it said. There was no mistaking where I had just arrived.

Saddam’s face was everywhere then, a constant reminder of the consequences of stepping outside the boundaries of subservient Iraqi life. I remember clearly when I walked down the jetway from the Royal Jordanian plane at Saddam International Airport. “Down With the USA!,” it said. There was no mistaking where I had just arrived.

I was frightened and alone as I navigated my way through the maze of Iraqi controls for the foreign media. I was even afraid to close my eyes at night in my twin bed on a sixth-floor room at the Al Rashid Hotel. I knew someone was watching. Or listening. Or both.

On that trip, I met good people who had given up on life after years of conflict and punishing sanctions that robbed Iraq of material goods and normalcy of life.

A doctor who had no access to modern medicine, current journals or technology. A professor who sat under empty bookshelves – he had sold them all to feed his family. And a bookseller who hoped to make a living hawking outdated computer science books along with “the Great Gatsby” and “War and Peace” on the sidewalks of Al Mutanabi Street.

Where were they all now, I wondered? How their hopes must have risen an plunged like the tides of the oceans. I know I will probably not find them again now – after a decade of war, a decade of convulsion.

But I cannot wait to see Baghdad again. The way it was without American tanks and Humvees. I am anxious to see how the Iraqi capital is faring a decade after the war began and forever changed the course of Iraqi history.

I leave Jerash, my face pressed against the car window, all the way back to Amman. Soon I will be in Iraq, where I spent so many months of my life covering the war. In the midst of tragedy, I came to know a land that I loved in a way that is not always understandable. Perhaps it was because I saw the very best of humanity in conditions that were the worst.

Now I am eager to be there again.