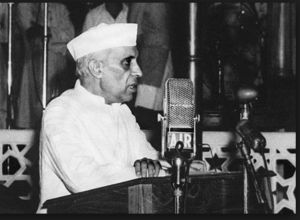

Today, on the 70th birthday of my homeland, I reread Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s evocative speech, delivered just before India gained independence from oppressive British rule.

At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom. A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance.

The speech still sends shivers down my spine.

A new star rises, the star of freedom in the East, a new hope comes into being, a vision long cherished materializes. May the star never set and that hope never be betrayed!

August 15, 1947. Freedom at midnight.

My mother’s family listened to the speech on the radio in Calcutta. My father’s family knew they would have to leave home in Dhaka and restart their lives in Calcutta.

India was no longer one. Its happiest moment was also one of its saddest.

In negotiating freedom, India’s Muslim leaders demanded a homeland of their own. So, from my homeland’s left and right sides was carved out a new nation: Pakistan, land of the pure.

Bengal, the land of my ancestors, was divided in two. Dhaka, the most populous city in East Bengal became a part of East Pakistan at that fateful stroke of the midnight hour. My father’s family was Hindu and they left their house on Bakshibajar Lane. They left childhood friends and everything that was familiar to travel through lush lands around the Ganges Delta to cross over into West Bengal, now a state in India.

Our next thoughts must be of the unknown volunteers and soldiers of freedom who, without praise or reward, have served India even unto death. We think also of our brothers and sisters who have been cut off from us by political boundaries and who unhappily cannot share at present in the freedom that has come. They are of us and will remain of us whatever may happen.

Read Pankaj Mishra on India at 70

Read Pankaj Mishra on India at 70

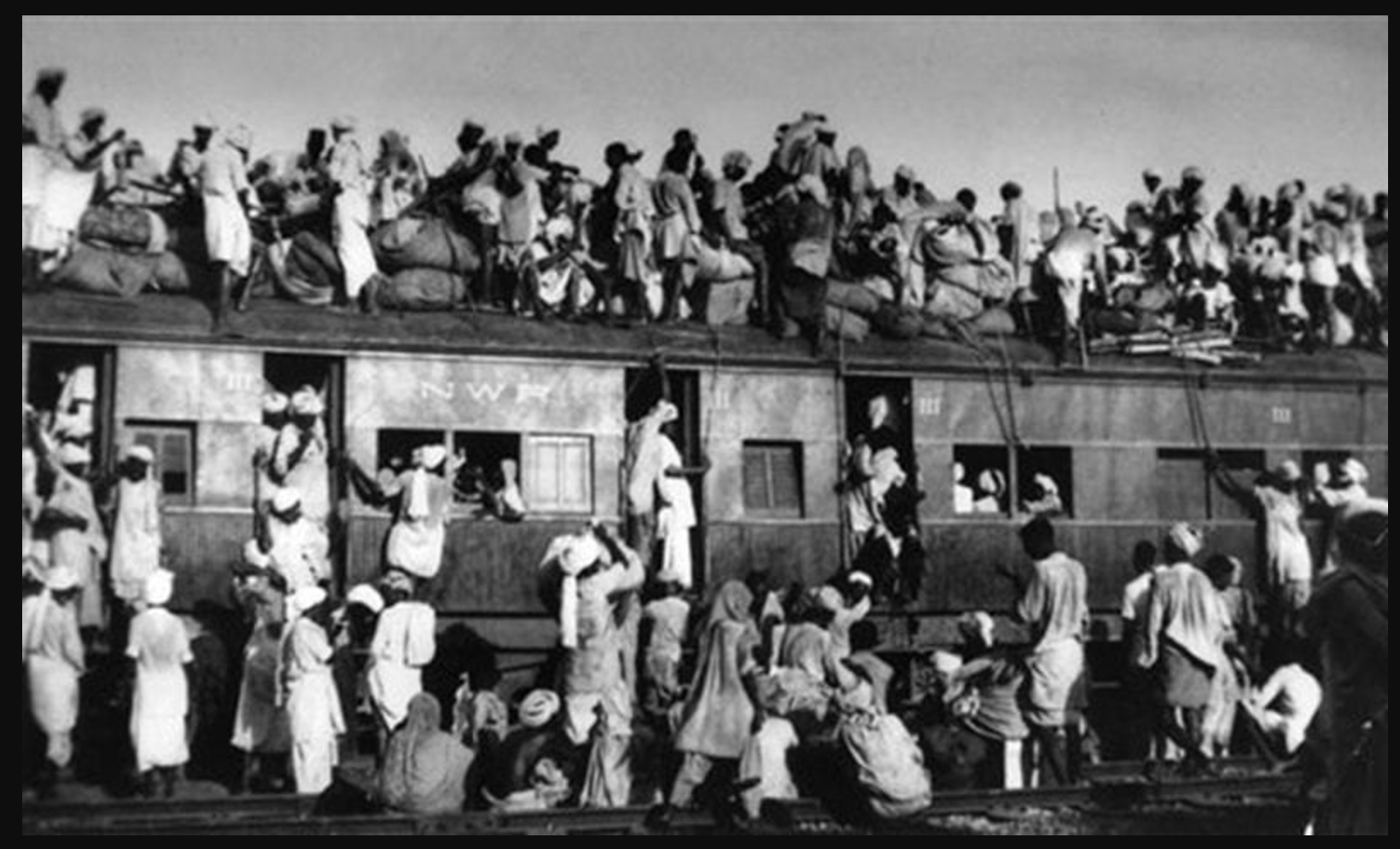

The partitioning of India gave way to one of the largest forced migrations of the 20

The partitioning of India gave way to one of the largest forced migrations of the 20th century. And though the leaders of the Indian independence movement took enormous pride in having successfully fomenting nonviolent revolution, the partitioning of India was anything but.

About 9 million Hindus and Sikhs moved to India and 5 million Muslims exited to Pakistan. That’s 14 million refugees.

Trains carrying Muslims from Delhi to Lahore arrived drowning in crimson rivers; bodies tumbling out at the station. Hindus killed Muslims. Muslims killed Hindus. Mahatma Gandhi’s dream became drenched with blood.

At least one million people were slaughtered; some believe that number is much higher.

My father’s family was lucky. They resettled in Calcutta, now Kolkata, without terrible loss.

But so many suffered and some of their stories are documented in an oral storytelling project called 1947 Archive.

Ajay Kumar De recorded his story on the 1947 Archive. He was born in Dhaka in 1935, 11 years after my father, and recalled how people irrespective of faith, lived together cooperatively.

He remembered a riot breaking out one day in 1950 and that men brandishing swords attached his school. The principal of the school held off the men and then, when trouble subsided, took the children back home himself, he said.

When the mob approached his house, someone put a hand over his mouth to keep him silenced. He saw the sword-carrying men climb over the wall of his house and attack people. Eventually, the mob left and De’s family sought refuge at a local firehouse, before escaping to West Bengal. He had no documents or belongings and started life from scratch. De went on to earn a Ph.D from Calcutta University, just like my father.

Partition, De said, had created a deep sense of enmity between people who once lived side by side.

Decades passed and my father’s siblings all returned to visit Dhaka, to the home they had been forced to flee, to the friends they had been forced to abandon. My father talked about his childhood and his beloved Dhaka but he could never quite get on a plane to go back. It was too painful, especially after his parents died and a pre-Partition life seemed familiar and alien all at once.

I visited Dhaka several times in the 1980s and 1990s and stayed with my uncle’s closest friends in Bangladesh. Motin Khan took me to the great house on Bakshibajar Lane, the one I had heard fabled stories about from my father. It stood before me, unimpressively small on a congested lane. And yet, I peered inside the metal gate, longing to know what life was like inside in 1924, when my father was born, the second eldest of five brothers and three sisters.

I stared at the cement and plaster grown old with the years and blackened by moisture. It was as though the place had fallen into deep sorrow, mourning a time that could never come back. I pictured my father as a boy, playing with his brothers and cousins, getting stung by hornets after pestering their nests and falling off bicycles ridden much too fast on dirt paths. And later, my father as a young man wanting to follow in his father’s footsteps by studying mathematics at Dhaka University. Sorry, Dacca University, as it was spelled then by the British.

Baba wrote me long letters about his childhood but by the time I was mature enough and curious enough to know more, he was ill with Alzheimer’s. I tried to learn as much as I could but our conversations were limited by his weakened cognitive abilities. I wish now that I had recorded my talks with Baba.

I believe it was 1994 when my uncle finally persuaded Baba to accompany him on a trip back to what has since become Bangladesh – land of the Bengalis. I wished I could have been there with them. What must it feel like to return home after so many decades?

Today, I wish my father were still alive so he and I could talk about that tryst with destiny and the price that was paid for it. So that we could remember all that was lost as we gained freedom at midnight.

Read a few of my stories on India:

The girl whose rape changed a country