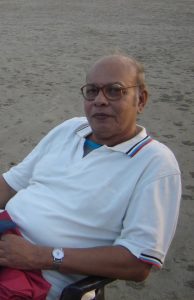

I have always been called the oldest among my cousins because the truly eldest of my generation were so much older than the rest of us, the sons of my eldest aunt, that they were not a part of our childhood gang. It was almost as though Gonuda and Manuda should have been our kakas and mamas, not dadas. Especially, Gonuda, who was only two years younger than my youngest uncle, Shonakaka.

Perhaps that was one reason I was so attached to Gonuda. He spoiled me as an uncle would. He played the role of elder brother with perfection, And I relished being the kid sister.

I remember lavish lunches of loochi (back in the day when I could eat them endlessly) and begun bhaja. Or jaunts to the Kolkata Port Trust Club to munch on fish fingers and down bottles of ice-cold Black Labels.

Gonuda loved to eat and though he was not a chef, he could speak like one about Bengali cuisine. He could tell you if a certain fish came from a pond or a river just by tasting it. He would argue with Shonakaka for hours on end about the merits of one way of preparing a dish over another. It was no surprise that when there was a wedding or any sort of celebration in the family, it was Gonuda who was called upon to set the menu, to supervise the caterers.

A day came when we learned Gonuda had developed kidney problems that would severely restrict his diet; that he would no longer be able to enjoy food. He was forced to curtail his protein intake, among other things, and was relegated to eating 50 grams of fish a day, probably one-tenth or so, I am guessing, of what he used to eat before.

For anyone, such a diet would be difficult. But that such a fate should befall a man who so loved to partake in the entire process of making a meal seemed like a cruel irony. My heart broke.

Food was one of the few things that Gonuda had in everyday life that brought him joy. He had suffered enough loss for a lifetime. His father and mother died young — I was not even 3 when my uncle passed away and I don’t even have any recollections of him. Then came the grossly premature passing of Gonuda’s wife, Monika, and their youngest son Shubho, who died suddenly in America after finishing college. Gonuda was never the same after Shubho’s death. I don’t know anyone who has ever recovered from the death of a child and a part of Gonuda was laid to rest along with his son.

Last year, we lost Gonuda’s younger brother and Manuda’s passing posed another big shock. It was too much for one man to bear, I thought.

Gonuda went on traversing life with a smile on his face and with an outpouring of affection in his heart. At a family remembrance on Zoom earlier today, many mentioned how Gonduda made them feel so loved.

But the sadness remained and occasionally, he could not but help let it surface. Occasionally, the tears flowed as though a dam had burst on a river kept in check. I never knew what to say in those moments. What can you say?

Gonuda lived simply by the principles he had adhered to all his life. Later, he also lived by routine. The older I get, the more I understand the comfort that a sameness can bring. And so it was that he would admonish me for knocking on his door too early, before he’d had a chance to fulfill his afternoon slumber.

We sipped tea together, with Bournvita biscuits, before heading out of Keyatala Lane to Southern Avenue and onto the paths that wind around the trees and gardens at Robindro Sarovar. In my youth, the lake waters were cleaner and Gonuda brought pieces of bread so that I could feed the ever-hungry carp.

We stopped for bhel-puri or phuchka, treats forbidden by my father, before racing the sunset on our way back home.

When I was even younger, we often visited Keyatala on weekends. Mostly on Sundays when Gonuda and Manuda would be at home. Or they’d visit my grandfather’s house in New Alipur, where there were so many of us for Sunday lunch that we would eat in batches and then plop down with satiated bellies on hard beds. Sometimes, Gonuda, took me to see a Bangla matinee at Priya cinema. Like Satyajit Ray’s “Goopy Gyne, Bagha Byne.” It wasn’t that hard back then to navigate Rash Behari Avenue when all of Gariahat shuttered for siesta and a hush fell on the streets amid the afternoon heat.

I traveled to India for the first time by myself in 1978, the year that Manuda was married. I stayed at New Alipur but spent many hours at Keyatala with Gonuda and Monikaboudi. I had told Gonuda how my friends in Florida coveted hand-embroidered clothes. This was, of course, long before the explosion of global trade that made it possible to buy everything Indian in America.

A few days before I was to return to Tallahassee, Gonuda arrived at New Alipur with a jute shopping bag full of presents for me. Among them were two cotton blouses, hand-embroidered in colorful thread. He had searched high and low in Gariahat shops and street stalls brimming with saris and salwars to find tops I could wear with my jeans – hardly an easy task back then.

One blouse was white and grew dingy enough to get tossed years ago but I still have the red one. I can’t wear it anymore but I can’t give it away, either. It hangs in my closet as memorial, a reminder of a happier time.

The Kolkata of my youth vanishes a bit more by the day. By that, I don’t mean the myriad changes that have come at dizzying speed. Cars, malls, satellite television and all the things that helped make India what is today.

For me, the pillars on which home stood are fast disintegrating. The people I loved most are gone. Pishi left us earlier this year. And now, Gonuda.

I don’t even know how to imagine my next trip back to the place that I love. I don’t think I want to.

I’m so sorry Moni about your loss of your wonderful Gonuda. I’m having a cry myself, feeling like I really missed out meeting such a caring, warm person. But the beautiful way you describe this time in your life and who he was pulls at my heart deeply. Love you, Moni. Sorry that another loving pillar has passed.

Beautifully written as always Chumki!